I. Introduction to the U.S. Bond Market

A. Defining the Bond Market: A Marketplace for Debt

The bond market, often referred to by alternative names such as the debt market, fixed-income market, or credit market, represents the collective global environment where debt securities are originated (issued) and subsequently traded among participants. Its fundamental purpose is to act as a conduit, channeling capital from entities possessing surplus funds (savers or investors) to those requiring funds (issuers) for various projects or operational needs.

At the heart of this market lies the bond itself. A bond is a type of debt security, effectively functioning as an IOU, issued by an organization such as a corporation, government entity, or government agency. In exchange for capital provided by the bond purchaser (the lender or bondholder), the issuer makes a binding promise. This promise typically involves repaying the original amount borrowed, known as the principal or face value (par value), on a specified future date (the maturity date). Additionally, most bonds entail regular, periodic interest payments, referred to as coupon payments, made to the bondholder throughout the bond’s life until maturity. Consequently, bondholders assume the role of creditors or lenders to the entity that issued the bond.

It is crucial to distinguish bonds from stocks. While bonds represent a debt obligation or a loan to the issuer, stocks (equities) represent an ownership stake in a company. This fundamental difference influences their risk and return characteristics. Because the terms of a bond (face value, coupon rate, maturity date) are generally fixed and known in advance, the market value of a bond typically fluctuates within a more constrained range compared to stocks, whose value is tied to the issuing company’s performance and market sentiment.

While bonds are the most prominent instruments, the bond market encompasses a variety of debt securities, including shorter-term instruments like bills and notes, as well as other debt forms like debentures. This diversity caters to the varying funding needs of issuers and the investment horizons and risk appetites of investors.

B. Fundamental Purpose: Connecting Capital Providers and Users

The core economic function of the bond market is to efficiently facilitate the transfer of capital between those who have it and those who need it. It acts as a critical intermediary, connecting investors seeking returns on their capital with issuers requiring funds to finance their activities.

This mechanism is vital for both the public and private sectors. Governments at all levels—federal, state, and local—rely heavily on the bond market to raise capital. They issue bonds to finance essential public expenditures, such as building and maintaining infrastructure (roads, schools, bridges, sewer systems), funding social programs, covering budget deficits, and repaying existing debts. Similarly, corporations utilize the bond market extensively to secure funding for a wide array of business purposes. These include financing ongoing operations, investing in expansion projects (like new manufacturing facilities or product lines), funding research and development, making acquisitions, buying back company stock, or refinancing older, more expensive debt.

The efficiency of this capital transfer process is paramount. Well-functioning, efficient capital markets, including the bond market, strive to connect capital providers and users seamlessly. Ideally, this efficiency translates into lower borrowing costs for issuers over time, as they can access needed funds more readily and competitively. Simultaneously, it allows investors to identify and access suitable investment opportunities that align with their risk tolerance and return objectives, thereby deploying their capital productively.

C. Scale and Significance of the U.S. Bond Market

The U.S. bond market is not merely significant; it is colossal in scale and scope, playing a dominant role both domestically and globally. Globally, the total value of outstanding debt securities was estimated at $119 trillion in 2021, with the U.S. market comprising a substantial portion of this total, estimated at $46 trillion in the same year. More recent data indicates the scale continues to be immense, with total U.S. fixed income outstanding (excluding certain securitized products like Mortgage-Backed Securities and Asset-Backed Securities) reaching $46.9 trillion by the end of the fourth quarter of 2024.

This vast market is composed of several key segments. As of late 2024 / early 2025, U.S. Treasury securities represented the largest single component, with approximately $28.3 trillion outstanding. Corporate bonds formed the second-largest segment at roughly $11.2 trillion outstanding. Municipal bonds accounted for about $4.2 trillion , and federal agency securities comprised over $2.0 trillion. Issuance volumes are equally staggering, reflecting the continuous need for capital; total U.S. fixed income issuance reached $2.9 trillion in the first quarter of 2025 alone.

The U.S. market’s dominance is clear, historically accounting for around 39% of the global bond market. Furthermore, the broader global credit market, which encompasses both bonds and bank loans, is estimated to be roughly three times the size of the global equity market, highlighting the fundamental importance of debt financing in the modern economy.

Within this landscape, the U.S. Treasury market holds a unique position. It is widely regarded as the largest and most liquid government securities market in the world. Its functions extend beyond simply financing the U.S. government; it plays a central role in the implementation of monetary policy by the Federal Reserve and serves as a critical benchmark for pricing countless other financial instruments, both within the U.S. private sector and across international markets.

The sheer magnitude of the U.S. bond market, exceeding $46 trillion in outstanding value, underscores its systemic importance. It is not merely a venue for trading debt but a foundational element of the U.S. and global financial architecture. Its size implies that significant disruptions, shifts in investor sentiment, or changes in liquidity within this market can have profound and far-reaching consequences, potentially impacting financial stability across the entire economic system. The health and smooth functioning of the bond market are, therefore, critical for overall economic well-being.

Furthermore, the market’s composition reveals its diversity. It is not a single entity but a collection of distinct segments—Treasuries, municipals, corporates, agency debt, mortgage-backed securities (MBS), asset-backed securities (ABS), and more. Each segment features different issuers, serves different purposes, carries unique risk characteristics, and attracts different types of investors. This heterogeneity allows for tailored financing solutions for borrowers and diverse investment strategies for lenders, but it also introduces layers of complexity that participants must navigate. Understanding the specific dynamics within each segment is essential for effective market analysis and investment management.

Comparing the bond market to the equity market also provides valuable context. The fact that the global credit market (bonds plus loans) dwarfs the global equity market suggests the immense role debt financing plays globally. While stocks represent ownership, bonds represent loans. Companies strategically choose between issuing debt (bonds) and equity (stocks) based on factors like prevailing market conditions, the relative cost of capital, and the desire to avoid diluting existing shareholders. The bond market’s vast size indicates that debt is a primary and often preferred method for raising capital for both governments and corporations under many circumstances.

II. Key Participants in the Bond Market

The functioning of the bond market relies on the interaction of several key groups of participants, each playing a distinct role in the ecosystem of debt issuance and trading.

A. Issuers: Borrowing Entities

Issuers are the entities that need to raise capital and do so by selling (issuing) bonds or other debt instruments into the market. They are the borrowers in the transaction. The major categories of issuers include:

- Governments: The U.S. federal government, acting through the Department of the Treasury, is the single largest issuer in the U.S. bond market. It issues Treasury securities—Bills, Notes, and Bonds—to finance the nation’s operations, fund social programs, invest in infrastructure, cover budget deficits, and manage existing government debt. Additionally, various Federal Agencies, such as the Government National Mortgage Association (GNMA or “Ginnie Mae”), issue securities that are explicitly backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government. Government-Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs), like the Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA or “Fannie Mae”) and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (FHLMC or “Freddie Mac”), also issue substantial amounts of debt (often called agency bonds) primarily related to the housing market. While GSE debt is not explicitly guaranteed by the federal government, it carries an implicit backing due to their public mission and charter.

- Municipalities: This broad category includes state governments, cities, counties, school districts, public utility districts, publicly owned airports and seaports, special-purpose districts, and other government-owned or authorized entities. They issue municipal bonds, commonly known as “munis,” primarily to raise funds for public infrastructure projects like building schools, highways, bridges, hospitals, and water/sewer systems. Munis may also be issued to cover general operating expenses or day-to-day obligations. In some cases, a municipal entity acts as a “conduit issuer,” issuing bonds on behalf of a third party, often a non-profit organization like a hospital or university, which is ultimately responsible for repayment.

- Corporations: Businesses of all sizes, from large multinational corporations to smaller companies, issue corporate bonds. They use the proceeds for a variety of purposes, including funding day-to-day operations, financing capital expenditures (like building new plants or buying equipment), expanding product lines, funding research and development, making acquisitions, buying back their own stock, or refinancing existing debt, potentially at more favorable interest rates. Corporate issuers span various sectors, including financial services, public utilities, energy, industrials, telecommunications, and real estate.

- Other Issuers: Banks are also significant issuers in the bond market, ranging from local community banks to large international and supranational institutions like the European Investment Bank.

B. Investors/Buyers: Lenders and Capital Providers

Investors, also referred to as purchasers or bondholders, are the individuals and entities that buy bonds, thereby lending money to the issuers. As bondholders, they become creditors to the issuing entity. Key groups of investors include:

- Institutional Investors: This is a major category comprising large organizations that manage substantial pools of capital. Examples include mutual funds, pension funds (both private and public), hedge funds, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), insurance companies, endowments, and sovereign wealth funds. These institutions are dominant players, particularly in the highly liquid U.S. Treasury market.

- Individual Investors (Retail Investors): Individuals participate in the bond market both directly and indirectly. Direct participation involves purchasing individual bonds, such as U.S. Treasury securities through the TreasuryDirect platform or buying municipal and corporate bonds through brokerage accounts. U.S. Savings Bonds (Series EE and I) are specifically designed for purchase by individuals. Indirect participation, which is more common for individuals, occurs through investing in bond mutual funds or bond ETFs, which hold diversified portfolios of bonds.

- Governments: Governments themselves are significant purchasers of bonds. This includes domestic government entities and, notably, foreign governments and central banks, which often hold large amounts of U.S. Treasury securities as part of their foreign exchange reserves resulting from international trade. The U.S. Federal Reserve is also a major holder of Treasury and agency securities, acquired through its monetary policy operations.

- Corporations: Companies also invest surplus cash in bonds as part of their treasury management operations.

Investors are motivated to purchase bonds for several reasons. A primary attraction is the potential for regular, predictable income through periodic coupon payments. Bonds also serve as a tool for portfolio diversification, as their returns often move differently (sometimes inversely) compared to stocks, potentially reducing overall portfolio volatility. Many investors view bonds, particularly government bonds, as relatively safe investments compared to equities, offering capital preservation. Specific types of bonds offer unique advantages, such as the potential tax-exempt income from municipal bonds, which is particularly attractive to investors in higher tax brackets.

C. Intermediaries: Facilitating Transactions

Intermediaries are crucial entities that facilitate the flow of bonds and capital between issuers and investors, particularly in the complex and often decentralized bond market structure.

- Dealers / Broker-Dealers: These firms, predominantly investment banks and other large financial institutions, are central to bond market activity, especially in the Over-the-Counter (OTC) market where most bonds trade. They act as market makers, providing liquidity by quoting prices at which they are willing to buy (bid) and sell (ask) bonds, often trading from their own inventory (principal trading). They also act as agents, executing trades on behalf of clients. Dealers provide essential services including research, sales support, trading execution, and structuring complex debt products. The vast majority of daily trading volume in the U.S. bond market occurs between these dealers and large institutional investors.

- Underwriters: In the primary market (where new bonds are issued), underwriters play a critical role. Typically investment banks or syndicates (groups) of investment banks, they are hired by issuers to manage the process of selling new bond offerings to investors. Their functions include advising the issuer on structuring the bond (terms, size, timing), preparing legal documentation such as the prospectus, gauging investor interest (book-building), assisting in the price discovery process, and ultimately distributing the bonds to the initial buyers. By forming syndicates, underwriters can share the financial risk associated with guaranteeing the sale of a large bond issue.

- Other Participants: A range of other entities provide essential services that support the bond market ecosystem:

- Credit Rating Agencies: Firms like Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s (S&P), and Fitch provide independent assessments of the creditworthiness of bond issuers and specific bond issues. These ratings (e.g., AAA, BB) give investors an indication of the likelihood of default and significantly influence a bond’s yield.

- Legal Counsel: Law firms specialize in drafting the complex legal documents required for bond issuance (indentures, prospectuses) and provide legal advice to issuers and underwriters throughout the process.

- Clearing Agencies: Organizations like the National Securities Clearing Corporation (NSCC) and the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation (FICC) act as central counterparties, comparing, clearing, and settling trades between buyers and sellers, reducing counterparty risk.

- Depositories: Entities like The Depository Trust Company (DTC) hold securities certificates (mostly electronically) on behalf of participants, maintain ownership records, and facilitate the transfer of positions.

- Exchanges and Alternative Trading Systems (ATSs): While most bonds trade OTC, some, primarily corporate bonds, are listed and traded on formal exchanges or ATSs.

- Regulators: Organizations like the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) and the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB) establish rules and oversee the conduct of broker-dealers and the trading of corporate and municipal securities, respectively. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) provides overall market oversight.

The bond market functions as a complex ecosystem characterized by a high degree of interdependence among its participants. Issuers depend on investors for capital and rely on intermediaries like underwriters and dealers for market access, distribution, and ongoing liquidity. Investors need issuers to provide investment opportunities that meet their risk/return objectives and rely on intermediaries for access to these opportunities, market information, liquidity, and transaction execution. Intermediaries, in turn, derive their business from serving the needs of both issuers and investors. This interconnectedness means that stress or capacity constraints in one part of the system—such as reduced risk appetite among dealers or a sudden withdrawal of investor demand—can quickly ripple through and impact the functioning of the entire market.

Governments, particularly the U.S. Treasury, occupy a uniquely influential position within this ecosystem. They are not only the largest issuers of debt , setting the benchmark “risk-free” rate, but are also significant investors and purchasers of debt securities. Furthermore, through the actions of the Federal Reserve, the government exerts powerful influence over interest rates and market liquidity via monetary policy. This multifaceted involvement gives government actions—whether related to borrowing levels, regulatory changes, or monetary policy shifts—an outsized impact on bond market dynamics, pricing, and overall stability.

The inherent complexity and the predominantly OTC nature of much of the bond market can lead to information asymmetries, where some participants have more or better information than others. Intermediaries, such as dealers providing research and facilitating price discovery , and credit rating agencies offering assessments of creditworthiness , play a crucial role in attempting to bridge these information gaps. Their analyses and opinions help market participants value securities and assess risk. However, it is important to recognize that these intermediaries operate with their own incentives, and their outputs (research, ratings) represent opinions that carry their own potential biases or limitations.

Comparison of Major U.S. Bond Types

| Characteristic | U.S. Treasury Securities | Municipal Bonds (GO) | Municipal Bonds (Revenue) | Corporate Bonds (Investment Grade) | Corporate Bonds (High Yield) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Issuer | U.S. Treasury Department | State/Local Governments | State/Local Government Entities, Authorities | Corporations (Strong Credit) | Corporations (Weaker Credit) |

| Primary Purpose | Fund Federal Government | Fund Public Projects/General Needs | Fund Specific Revenue-Generating Projects | Fund Business Operations/Growth | Fund Business Operations/Growth |

| Credit Risk | Lowest (Virtually None) | Low to Moderate | Moderate to Higher | Moderate | High |

| Federal Tax on Interest | Taxable | Generally Exempt | Often Exempt (Varies) | Taxable | Taxable |

| State/Local Tax on Interest | Exempt | Often Exempt (In-State) | Often Exempt (In-State) | Taxable | Taxable |

| Typical Yield Level | Lowest | Low (Higher After-Tax) | Low to Moderate | Moderate | Highest |

| Typical Liquidity | Highest | Moderate to Low | Moderate to Low | High to Moderate | Moderate to Low |

III. Major Types of Bonds in the U.S. Market

The U.S. bond market offers a wide array of debt securities, catering to different issuer needs and investor preferences regarding risk, return, maturity, and tax treatment. Understanding the characteristics of the major bond types is essential for navigating this market.

A. U.S. Treasury Securities (Bills, Notes, Bonds, TIPS): The Benchmark for Safety

Issued directly by the U.S. Department of the Treasury, these securities are used to finance the federal government’s activities and manage its debt. They are backed by the “full faith and credit” of the U.S. government, meaning the government pledges its full resources to pay interest and principal. This backing makes them universally regarded as the safest type of bond investment available, carrying the lowest level of credit or default risk.

Due to their perceived safety, U.S. Treasury securities serve as a fundamental benchmark for the entire global financial system. Their yields are often referred to as “risk-free rates,” and the yields on virtually all other types of bonds (municipal, corporate, international) are typically evaluated and priced relative to Treasuries of comparable maturity, with the difference (spread) reflecting the additional perceived risk.

Treasury securities are issued in various maturities:

- Treasury Bills (T-Bills): These are short-term debt instruments with maturities of one year or less (common maturities are 4, 8, 13, 17, 26, and 52 weeks). T-Bills do not pay periodic coupon interest. Instead, they are sold at a discount to their face value and the investor receives the full face value at maturity. The difference represents the interest earned.

- Treasury Notes (T-Notes): These are intermediate-term securities with maturities ranging from two to ten years (specifically 2, 3, 5, 7, and 10 years). T-Notes pay a fixed rate of interest (coupon) semi-annually until maturity, at which point the principal (face value) is repaid. The yield on the 10-year Treasury Note is one of the most closely watched financial indicators globally, serving as a key benchmark for mortgage rates and reflecting broader economic sentiment.

- Treasury Bonds (T-Bonds): These are long-term debt securities, typically issued with maturities of 20 or 30 years. Like T-Notes, T-Bonds pay a fixed rate of interest semi-annually and return the principal at maturity.

- Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS): These securities are designed to protect investors from inflation. Their principal value is adjusted semi-annually based on changes in the Consumer Price Index (CPI). While they pay a fixed coupon rate, the actual interest payment varies because the rate is applied to the inflation-adjusted principal. At maturity, the investor receives the inflation-adjusted principal or the original principal, whichever is greater.

In terms of taxation, the interest earned on U.S. Treasury securities is subject to federal income tax but is exempt from state and local income taxes. This feature can be advantageous for investors residing in high-tax states.

New Treasury securities are issued through regular public auctions conducted by the Treasury Department. Investors, both institutional and individual, can participate in these auctions through banks or brokers, or directly via the TreasuryDirect online platform.

B. Municipal Bonds (Munis): Funding Public Projects

Municipal bonds, or “munis,” are debt securities issued by state and local governments and their authorized entities, such as cities, counties, states, public universities, hospitals, school districts, water and sewer authorities, airports, and toll road authorities.

The primary purpose of municipal bond issuance is to finance public infrastructure projects that benefit the community. Examples include building or repairing schools, roads, bridges, highways, hospitals, airports, and water treatment facilities. Less commonly, munis might be issued to cover general operating expenses or existing obligations.

There are two main types of municipal bonds, distinguished by the source of funds pledged for repayment:

- General Obligation (GO) Bonds: These bonds are backed by the full faith, credit, and general taxing power of the issuing government entity. Repayment comes from the issuer’s general funds or, in some cases, dedicated property taxes. Because they rely on the issuer’s ability to levy taxes, GO bonds are generally considered the safer category of municipal bonds.

- Revenue Bonds: These bonds are backed solely by the revenues generated from a specific project or source that the bonds financed. Examples include tolls collected from a bridge or highway, fees from a water utility, airport landing fees, or revenues from a public hospital. If the specific project fails to generate sufficient revenue, bondholders may not be repaid in full. Consequently, revenue bonds are typically considered riskier than GO bonds. This category also includes “private activity bonds,” which are issued by a municipality on behalf of a private entity (like a non-profit hospital or affordable housing developer) to finance specific qualified projects.

The most distinctive feature of municipal bonds is their tax treatment. The interest income earned from most municipal bonds is exempt from federal income tax. Furthermore, if the bondholder resides in the state where the bond was issued, the interest income may also be exempt from state and local income taxes. This potential “triple tax-exempt” status makes munis particularly attractive to investors in high tax brackets, as the after-tax return can be higher than that of a taxable bond with a higher pre-tax yield. However, it’s important to note that not all municipal bonds qualify for tax exemption; certain types, like some private activity bonds, may be subject to federal taxes (including the Alternative Minimum Tax). The tax advantage generally results in municipal bonds offering lower pre-tax yields compared to taxable bonds like corporates or Treasuries.

In terms of risk, municipal bonds generally fall between U.S. Treasuries and corporate bonds. While defaults have historically been rare compared to corporate bonds , they can and do occur, particularly during severe economic stress or if an issuer faces significant financial mismanagement. The credit risk varies widely depending on the specific issuer’s financial health, economic base, and the type of bond (GO vs. Revenue).

Liquidity in the municipal market can be lower compared to Treasuries or large corporate issues, especially for bonds from smaller or less frequent issuers. This means it might be harder to sell a muni quickly without affecting its price. Municipal bonds are typically issued in minimum denominations of $5,000. While most are fixed-rate, variable-rate structures like Variable Rate Demand Obligations (VRDOs) also exist, though they often have higher minimum investments. Like other bonds, munis may include call provisions allowing the issuer to redeem them before maturity, typically when interest rates have fallen.

C. Corporate Bonds: Financing Business Operations and Growth

Corporate bonds are debt securities issued by private and public corporations to raise capital. Unlike buying stock, purchasing a corporate bond does not grant ownership in the company; instead, the bondholder becomes a lender to the corporation.

Corporations issue bonds for numerous reasons, including funding ongoing operations, financing expansion projects, research and development, acquisitions, refinancing existing debt, or returning capital to shareholders via stock buybacks. They represent a major source of funding alongside bank loans and equity issuance.

The primary distinguishing feature of corporate bonds compared to government bonds is their higher level of credit risk, also known as default risk. Companies can face financial distress or even bankruptcy, potentially leading to delayed payments or losses for bondholders. The level of risk varies significantly depending on the issuing company’s financial stability, profitability, debt levels, industry outlook, and overall economic conditions. Credit rating agencies assess this risk and assign ratings to corporate bonds. In the event of bankruptcy, corporate bondholders generally have a higher claim on the company’s assets than common stockholders, meaning they are more likely to recover some of their investment.

To compensate investors for taking on this higher credit risk, corporate bonds typically offer higher interest rates (yields) compared to U.S. Treasury or municipal bonds of similar maturity.

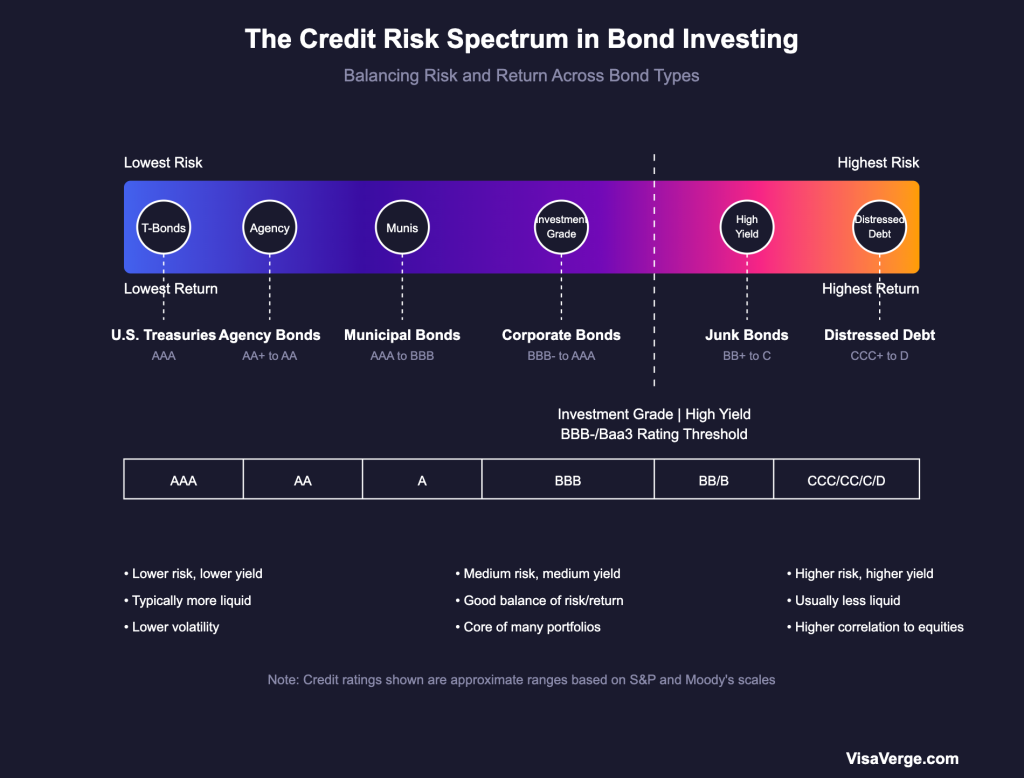

Corporate bonds are broadly categorized based on their credit quality:

- Investment Grade Bonds: These are issued by companies considered to have a relatively strong capacity to meet their debt obligations. They receive higher credit ratings (typically Baa3/BBB- or above from Moody’s/S&P/Fitch). While still carrying more risk than Treasuries, they are viewed as lower risk within the corporate bond universe.

- High-Yield Bonds (also known as “Junk Bonds” or “Speculative Grade”): These are issued by companies with lower credit ratings (below Baa3/BBB-). These issuers are perceived as having a higher probability of default. To attract investors despite the elevated risk, high-yield bonds offer significantly higher coupon rates and yields compared to investment-grade bonds. High-yield bonds tend to be more sensitive to economic downturns and exhibit a higher correlation with the stock market compared to investment-grade bonds.

Interest income received from corporate bonds is generally fully taxable at the federal, state, and local levels.

Liquidity varies in the corporate bond market. Bonds issued by large, well-known companies often trade actively and are relatively liquid, while bonds from smaller or less frequent issuers may have lower liquidity. Trading activity for corporate bonds is reported through FINRA’s TRACE system, providing transparency.

Corporate bonds typically have maturities of at least one year, often extending much longer. They can be structured in different ways: some are “secured,” meaning they are backed by specific company assets (collateral) like property or equipment, offering bondholders greater protection in case of default. Others are “unsecured” (often called debentures), backed only by the general creditworthiness of the issuer. Many corporate bonds include call provisions, allowing the issuer to redeem the bonds early, usually if interest rates fall. Some corporate bonds are “convertible,” giving the bondholder the option to convert the bond into a predetermined number of the company’s common stock shares under certain conditions.

D. Other Significant Bond Types

Beyond the “big three,” several other types of bonds play important roles in the U.S. market:

- Agency Bonds: Issued by U.S. federal government agencies (like Ginnie Mae) or Government-Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs like Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Federal Home Loan Banks). These entities often focus on specific sectors, particularly housing finance. Agency bonds generally carry very low credit risk due to explicit (for federal agencies) or implicit (for GSEs) government backing, though yields are typically slightly higher than Treasuries to reflect a small risk premium (e.g., political risk of charter changes). Interest income from agency bonds is often taxable at all levels (federal, state, and local).

- Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS): These are securities created by pooling together a large number of residential mortgages. The principal and interest payments made by the homeowners on the underlying mortgages are passed through to the investors who own the MBS. Major issuers or guarantors of MBS include Ginnie Mae, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac. The value and performance of MBS are tied not only to interest rates but also to the housing market, homeowner default rates, and prepayment speeds (homeowners refinancing or selling their homes early). The MBS market is substantial, with significant trading volumes.

- Asset-Backed Securities (ABS): Similar in structure to MBS, ABS are backed by pools of other types of financial assets, such as automobile loans, credit card receivables, student loans, equipment leases, or royalty payments. They allow lenders to bundle these loans and sell them to investors, freeing up capital to make new loans.

- U.S. Savings Bonds (Series EE and I): These bonds are specifically designed for individual investors and are purchased directly from the U.S. Treasury via the TreasuryDirect website, not typically traded on secondary markets. They are considered very safe, low-risk savings vehicles.

- Series EE Bonds: Earn a fixed rate of interest for up to 30 years. Bonds purchased currently are guaranteed to double in value over 20 years.

- Series I Bonds: Designed to protect against inflation. They earn a composite interest rate consisting of a fixed rate (set at issuance) and a variable inflation rate (adjusted semi-annually based on CPI).

- Both EE and I bonds have annual purchase limits per Social Security Number. Interest earned is subject to federal tax but exempt from state and local taxes. There’s also a potential federal tax exclusion if proceeds are used for qualified higher education expenses.

- Zero-Coupon Bonds: These bonds do not make periodic interest payments (no coupon). Instead, they are sold at a significant discount to their face value. The investor’s return is the difference between the discounted purchase price and the full face value received at maturity. Governments and corporations can issue zero-coupon bonds. They are often used for long-term goals where periodic income is not needed.

E. Comparison of Major U.S. Bond Types

The following table provides a comparative overview of the key characteristics of the major U.S. bond types discussed:

| Characteristic | U.S. Treasury Securities | Municipal Bonds (General Obligation) | Municipal Bonds (Revenue) | Corporate Bonds (Investment Grade) | Corporate Bonds (High Yield / Junk) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Issuer | U.S. Treasury Dept. | State/Local Governments | State/Local Gov’t Entities, Authorities | Corporations (Strong Credit) | Corporations (Weaker Credit) |

| Primary Purpose | Fund Federal Gov’t | Fund Public Projects/General Needs | Fund Specific Revenue-Generating Projects | Fund Business Operations/Growth | Fund Business Operations/Growth |

| Credit Risk (General) | Lowest (Virtually None) | Low to Moderate | Moderate to Higher | Moderate | High |

| Federal Tax on Interest | Taxable | Generally Exempt | Often Exempt (Varies) | Taxable | Taxable |

| State/Local Tax on Int. | Exempt | Often Exempt (In-State) | Often Exempt (In-State) | Taxable | Taxable |

| Typical Yield Level | Lowest | Low (Higher After-Tax) | Low to Moderate | Moderate | Highest |

| Typical Liquidity | Highest | Moderate to Low | Moderate to Low | High to Moderate | Moderate to Low |

The diverse range of bond types available clearly illustrates the fundamental financial principle of the risk-return trade-off. U.S. Treasuries, backed by the full faith and credit of the government, represent the lowest end of the risk spectrum and consequently offer the lowest yields. At the opposite end, high-yield corporate bonds carry substantial default risk due to the weaker financial standing of their issuers, and investors demand significantly higher yields as compensation for bearing this risk. Municipal bonds and investment-grade corporate bonds occupy the middle ground, offering varying levels of risk and corresponding yields. Investors must carefully assess their own risk tolerance and return requirements when selecting among these options, effectively choosing their position along this risk-return continuum.

Taxation emerges as another critical differentiator, significantly influencing investment decisions and market segmentation. The federal tax exemption (and potential state/local exemption) granted to most municipal bond interest creates a distinct advantage, particularly for individuals in higher income tax brackets. This tax benefit allows municipal bonds to offer competitive after-tax yields even when their pre-tax yields are lower than comparable taxable bonds. Similarly, the exemption of Treasury interest from state and local taxes provides a benefit over fully taxable corporate bonds. These tax rules shape investor demand and influence the relative pricing of different bond types.

The existence of securitized products like Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) and Asset-Backed Securities (ABS) introduces another layer of complexity to the bond market. Unlike traditional bonds that represent a loan to a single entity, these instruments derive their value from the cash flows of large pools of underlying assets (mortgages, auto loans, etc.). Their performance is therefore dependent not only on prevailing interest rates but also on factors specific to the underlying assets, such as borrower default rates, prepayment speeds (for mortgages), and the correlations among assets within the pool. Analyzing these securities requires different methodologies and an understanding of risks beyond traditional credit and interest rate risk, such as prepayment risk and the dynamics of the specific sector backing the security (e.g., the housing market for MBS).

Key Participants in the Bond Mar

| Participant Type | Role | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Issuers (Governments) | Borrow money by issuing bonds to finance operations, infrastructure, and other needs | U.S. Treasury, Federal Agencies, State/Local Governments, GSEs (Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac) |

| Issuers (Corporations) | Raise capital for operations, expansion, acquisitions, refinancing | Companies across sectors (financial, utilities, energy, industrials, telecommunications, real estate) |

| Institutional Investors | Purchase bonds for income, capital preservation, and portfolio diversification | Mutual funds, pension funds, insurance companies, hedge funds, ETFs, endowments, sovereign wealth funds |

| Individual Investors | Purchase bonds directly or indirectly for income and portfolio diversification | Retail investors buying through brokerages, TreasuryDirect, or investing in bond funds/ETFs |

| Dealers/Broker-Dealers | Provide liquidity, execute trades, make markets in the OTC market | Investment banks, large financial institutions |

| Underwriters | Manage the process of issuing new bonds in the primary market | Investment banks and syndicates |

| Credit Rating Agencies | Assess and rate the creditworthiness of issuers and specific bond issues | Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s (S&P), Fitch |

| Regulators | Oversee and regulate market activities and participants | SEC, FINRA, MSRB |

IV. How the Bond Market Operates

Understanding the mechanics of how bonds are issued and traded is crucial to comprehending the market’s dynamics and pricing. The bond market operates through two main segments: the primary market and the secondary market.

A. The Primary Market: Issuing New Debt

The primary market is the segment where new debt securities are created and sold for the first time. It is through this market that issuers raise fresh capital directly from investors. The process of issuance varies depending on the type of issuer:

- Treasury Issuance: The U.S. Treasury employs a regular auction system to sell its Bills, Notes, and Bonds. Auctions are announced in advance with details on the amount and type of security being offered. Participants submit bids, which fall into two categories:

- Non-Competitive Bids: Bidders agree to accept the yield or discount rate determined by the auction. These bids are typically filled in full up to a certain maximum amount (e.g., $10 million per auction). This method is commonly used by individual investors (often through TreasuryDirect) and smaller institutions who prioritize obtaining the security over achieving a specific price.

- Competitive Bids: Bidders specify the minimum yield (or maximum discount rate) they are willing to accept. The Treasury fills bids starting with the lowest yields (most aggressive bids) until the offering amount is reached. The highest accepted yield determines the rate for all successful bidders (both competitive and non-competitive) in a single-price auction format. Competitive bidders whose specified yield is above the auction-determined yield will not receive any securities, while those at the highest accepted yield may receive only a portion of their bid amount. This method is primarily used by large institutional investors and dealers.

- Corporate and Municipal Issuance: When corporations or municipalities issue bonds, they typically enlist the services of one or more investment banks to act as underwriters. The underwriters advise the issuer on the terms of the bond, help prepare the necessary legal documentation (including the prospectus, which details the offering and issuer information), market the bonds to potential investors, and manage the sale process. Often, large bond issues are handled by a “syndicate” of underwriters who collaborate to distribute the bonds and share the associated risks. The underwriters purchase the bonds from the issuer (or guarantee their sale) and then resell them to investors, earning fees or a spread for their services. This process involves gauging investor demand (book-building) to help determine the appropriate interest rate (coupon) for the new bonds.

B. The Secondary Market: Trading Existing Bonds

Once bonds have been issued in the primary market, they can be bought and sold among investors in the secondary market. This market provides crucial liquidity, allowing bondholders to sell their investments before the scheduled maturity date if they need cash or wish to adjust their portfolio.

A defining characteristic of the U.S. bond market is that the vast majority of trading occurs in a decentralized Over-the-Counter (OTC) market, rather than on centralized public exchanges like those used for stocks. In the OTC market, transactions are negotiated directly between two parties, typically large institutions and broker-dealers, often via electronic communication networks or telephone. While a small number of corporate bonds might be listed on exchanges like the NYSE, this is the exception rather than the rule.

Broker-dealers are central figures in the OTC secondary market. They act as intermediaries, facilitating trades by matching buyers and sellers (acting as agents) or by trading directly with investors from their own inventory (acting as principals or market makers). When acting as principals, dealers quote bid prices (at which they will buy) and ask prices (at which they will sell). The difference between these prices is the bid-ask spread, which represents a cost to investors and potential profit for the dealer. The willingness and ability of dealers to hold bonds in inventory and provide continuous quotes are critical determinants of market liquidity.

Given the decentralized nature of OTC trading, transparency can be a challenge. To address this, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) operates the Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE). TRACE requires broker-dealers to report transaction details (price, volume, time) for trades in eligible fixed-income securities (including corporate bonds, agency debt, and now Treasuries) shortly after execution. This reported data is then disseminated publicly, providing valuable post-trade transparency that helps investors gauge market prices, assess liquidity, and allows regulators to monitor activity. For the municipal bond market, similar transparency is provided through the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board’s (MSRB) Electronic Municipal Market Access (EMMA) system.

Bonds are typically quoted and traded based on their price, expressed as a percentage of their face value (par value, usually $1,000). A price of 100 means the bond is trading at par, 98 means 98% of par (a discount), and 102 means 102% of par (a premium). While bonds have a face value often in $1,000 increments, actual trading sizes vary significantly. Retail trades might be smaller, but institutional trades often occur in large blocks, with trades under $100,000 sometimes considered “odd lots” by dealers. Liquidity—the ease with which a bond can be bought or sold quickly without significantly affecting its price—can vary dramatically depending on the specific bond issue, its size, the issuer’s prominence, and overall market conditions.

C. Bond Pricing, Coupon Rates, and Yields: The Interplay

Understanding the relationship between a bond’s price, its coupon rate, and its yield is fundamental to bond market mechanics.

- Coupon Rate: This is the nominal annual interest rate stated on the bond certificate or indenture, determined by the issuer at the time of issuance. It represents the fixed percentage of the bond’s face value that the issuer promises to pay in interest each year. For most U.S. Treasury and corporate bonds, this annual amount is paid in two semi-annual installments.

- Bond Price: This is the price at which a bond is currently trading in the secondary market. It fluctuates based on supply and demand, influenced primarily by changes in prevailing market interest rates and the perceived creditworthiness of the issuer. As noted, it’s quoted as a percentage of par value.

- Yield: Yield represents the total return an investor expects to receive from holding a bond. While several yield measures exist, the most comprehensive and commonly used is the Yield-to-Maturity (YTM). YTM is the total annualized rate of return anticipated on a bond if the investor holds it until it matures. It takes into account not only the periodic coupon payments but also any capital gain or loss realized if the bond was purchased at a discount or premium to its face value, as well as the reinvestment of coupon payments at the YTM rate. Another simpler measure is the Current Yield, calculated by dividing the annual coupon payment by the bond’s current market price.

The most critical concept governing bond pricing is the inverse relationship between bond prices and bond yields (market interest rates). When prevailing interest rates in the market rise, newly issued bonds will offer higher coupon rates to attract investors. This makes existing bonds with lower, fixed coupon rates less attractive by comparison. To compete, the market price of these existing bonds must fall below their face value (trade at a discount). This price decline increases their effective yield (YTM) for a new buyer, bringing it in line with the higher yields available on new issues. Conversely, when market interest rates fall, new bonds are issued with lower coupon rates. Existing bonds with higher fixed coupons become more desirable. Increased demand pushes their market prices above face value (trade at a premium), which lowers their effective yield (YTM) for a new buyer to match the lower prevailing market rates.

A bond’s YTM in the secondary market is determined by several interacting factors: its fixed coupon rate, its current market price, the remaining time until its maturity date, and assumptions about the rate at which the received coupon payments can be reinvested over the bond’s life. However, the primary driver of changes in a bond’s price and yield after issuance is the fluctuation in overall market interest rates, which are themselves influenced by factors like inflation expectations, economic growth prospects, and central bank monetary policy.

D. The Concept of Duration: Measuring Interest Rate Sensitivity

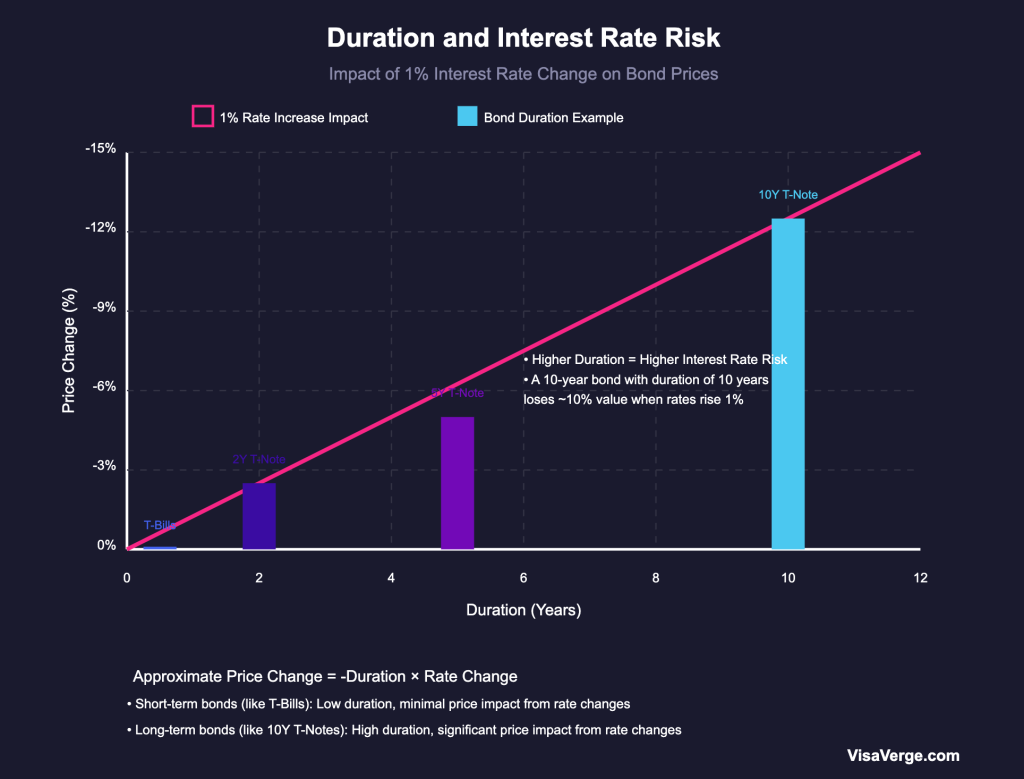

While maturity indicates the length of time until a bond’s principal is repaid, duration is a more precise measure of how sensitive a bond’s price is to changes in interest rates. It is crucial to understand that duration is not the same as maturity, although maturity is a key input in its calculation. Technically, duration represents the weighted-average time (in years) until the bond’s cash flows (coupon payments and principal repayment) are received, with cash flows received sooner weighted more heavily.

In practical terms, duration provides an estimate of the percentage change in a bond’s price for a 1 percentage point (100 basis points) change in market interest rates. For example, a bond with a duration of 7 years would be expected to decrease in price by approximately 7% if market interest rates rise by 1%, and increase in price by about 7% if rates fall by 1%. This makes duration a key metric for assessing and managing interest rate risk.

Several factors influence a bond’s duration:

- Maturity: Generally, the longer the time until maturity, the higher the duration, meaning long-term bonds are more sensitive to interest rate changes than short-term bonds.

- Coupon Rate: The higher the bond’s coupon rate, the lower its duration. This is because a higher coupon means the investor receives more of the bond’s total cash flow earlier, reducing the weighted-average time to receipt. Zero-coupon bonds, which pay no interest until maturity, have durations equal to their maturities.

- Yield: The current yield-to-maturity also affects duration; higher yields generally lead to lower duration, and vice versa.

- Call Features: Bonds with call provisions (allowing early redemption by the issuer) can have complex duration characteristics, as the possibility of being called effectively shortens the expected life of the bond, particularly when rates fall.

Investors and portfolio managers use duration extensively to gauge the interest rate risk of individual bonds and entire bond portfolios. Bond mutual funds and ETFs typically report the average duration of their holdings in their fact sheets, allowing investors to compare the interest rate sensitivity of different funds.

The distinction between the primary and secondary markets highlights their different but complementary roles. The primary market focuses on capital formation—issuers raising funds. The secondary market focuses on liquidity and price discovery—investors trading existing securities. However, these markets are deeply interconnected. A liquid and efficient secondary market is essential for a healthy primary market. Investors are more willing to purchase new bond issues if they are confident they can easily sell them later in the secondary market if needed. Illiquidity or inefficiency in the secondary market increases the perceived risk for investors, which in turn raises borrowing costs for issuers in the primary market.

The prevalence of the Over-the-Counter (OTC) structure in the bond market has significant implications for liquidity. Unlike centralized stock exchanges with continuous order matching, bond market liquidity heavily depends on the willingness and capacity of numerous individual dealers to make markets by committing their own capital to hold inventory. During periods of market stress or heightened uncertainty, dealers may become more risk-averse, widen their bid-ask spreads, or reduce the amount of inventory they are willing to hold. This can lead to a rapid decline in market liquidity, making it difficult or expensive for investors to trade, potentially amplifying price volatility. This inherent structural feature makes liquidity risk a constant consideration for bond market participants.

The inverse relationship between bond prices and yields serves as the core adjustment mechanism for the bond market. Every piece of relevant news—be it economic data releases, inflation reports, central bank communications, or geopolitical events—is filtered through this mechanism. Market participants assess how the new information might impact future economic growth, inflation, and interest rates, and they adjust their buying and selling behavior accordingly. This collective action causes bond prices to move up or down, forcing yields to adjust until the market reaches a new equilibrium reflecting the updated information and expectations. Duration quantifies the expected magnitude of this price adjustment for any given change in yield , making it a vital tool for understanding potential price volatility.

U.S. Treasury Securities Comparison

| Characteristic | Treasury Bills (T-Bills) | Treasury Notes (T-Notes) | Treasury Bonds (T-Bonds) | Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maturity Range | 1 year or less (4, 8, 13, 17, 26, 52 weeks) | 2 to 10 years (2, 3, 5, 7, 10 years) | 20 or 30 years | 5, 10, or 30 years |

| Interest Payment Method | Discount from face value (no periodic coupon) | Fixed coupon rate, paid semi-annually | Fixed coupon rate, paid semi-annually | Fixed coupon rate on inflation-adjusted principal, paid semi-annually |

| Inflation Protection | None | None | None | Principal adjusted for inflation based on CPI |

| Tax Treatment | Interest subject to federal tax, exempt from state/local tax | Interest subject to federal tax, exempt from state/local tax | Interest subject to federal tax, exempt from state/local tax | Interest and inflation adjustments subject to federal tax, exempt from state/local tax |

| Purchase Method | Treasury auctions, secondary market, TreasuryDirect | Treasury auctions, secondary market, TreasuryDirect | Treasury auctions, secondary market, TreasuryDirect | Treasury auctions, secondary market, TreasuryDirect |

| Key Investor Benefits | Short-term cash management, highest liquidity | Regular income, relatively low risk | Long-term income stream, relatively low risk | Protection against inflation risk |

V. Economic Significance of the U.S. Bond Market

The U.S. bond market is not merely a financial marketplace; it is a cornerstone of the U.S. economy, exerting profound influence on government finance, monetary policy, overall interest rates, and economic activity.

A. Funding the U.S. Government: The Role of Treasury Securities

The issuance of U.S. Treasury securities (Bills, Notes, and Bonds) is the primary mechanism through which the U.S. federal government finances its operations when tax revenues are insufficient to cover spending. This includes funding everything from national defense and social programs to infrastructure projects and paying interest on existing national debt. When the government runs a budget deficit (spends more than it collects in revenue), it borrows the difference by selling Treasury securities in the bond market.

The existence of a deep, liquid, and globally trusted market for U.S. Treasury securities is therefore of paramount importance to the U.S. government. It allows the government to borrow enormous sums of money relatively easily and typically at lower interest rates compared to other borrowers. The global demand for U.S. Treasuries, often seen as a safe-haven asset, helps keep borrowing costs manageable.

However, the scale of government borrowing has implications. Persistently large budget deficits and a growing national debt necessitate continuous, substantial issuance of new Treasury securities. If the supply of new Treasuries grows faster than investor demand, it can put upward pressure on Treasury yields (meaning higher borrowing costs for the government). Concerns about the long-term fiscal sustainability of the U.S., growing debt-to-GDP ratios, or shifts in demand from major holders (like foreign governments, whose share of holdings has declined from peaks ) can potentially impact the market’s capacity to absorb new debt smoothly and influence the level of interest rates the government must pay.

B. Influence on Interest Rates and Federal Reserve Monetary Policy

The bond market, particularly the U.S. Treasury market, plays a central role in the transmission of monetary policy and the determination of interest rates throughout the economy. Yields on Treasury securities act as benchmark rates against which many other interest rates are set or influenced.

The Federal Reserve (the Fed), as the central bank of the United States, is tasked with conducting monetary policy to achieve its dual mandate: promoting maximum employment and maintaining stable prices (low and stable inflation). The Fed utilizes several tools to influence financial conditions and steer the economy toward these goals:

- Federal Funds Rate Target: The Fed’s primary policy tool is setting a target range for the federal funds rate—the interest rate at which commercial banks lend reserves to each other overnight. Lowering the target range (“easing”) aims to reduce borrowing costs and stimulate economic activity, while raising the target range (“tightening”) aims to increase borrowing costs and curb inflation. Changes in the federal funds rate target quickly ripple through other short-term interest rates.

- Administered Rates: To keep the actual federal funds rate trading within the target range, especially in an environment of ample bank reserves, the Fed uses administered rates. The Interest on Reserve Balances (IORB) rate, paid to banks on funds held at the Fed, acts as a reservation rate, discouraging banks from lending below it. The Overnight Reverse Repurchase Agreement (ON RRP) facility offers certain non-bank institutions a place to deposit funds with the Fed at the ON RRP rate, acting as a floor for short-term rates. The Discount Rate, the rate at which banks can borrow directly from the Fed’s discount window, acts as a ceiling. The Fed typically moves these rates in tandem with the target range.

- Open Market Operations (OMO): Historically the main tool, OMO involves the Fed buying and selling U.S. Treasury securities in the open market. Buying securities injects money into the banking system, increasing reserves and typically lowering interest rates; selling securities withdraws money, decreasing reserves and typically raising rates. In the current ample reserves framework, OMOs are used more to maintain the level of reserves rather than to fine-tune the federal funds rate daily.

- Balance Sheet Policies (QE/QT): In recent decades, the Fed has also employed large-scale asset purchases, known as Quantitative Easing (QE), buying substantial amounts of longer-term Treasury securities and agency mortgage-backed securities. QE aims to directly lower longer-term interest rates and ease financial conditions when the federal funds rate is already near zero. Conversely, Quantitative Tightening (QT) involves reducing the Fed’s holdings of these securities (either by letting them mature without reinvesting or by actively selling them), which tends to put upward pressure on longer-term yields and tighten financial conditions.

The relationship between the Fed and the bond market is inherently two-way. Fed policy actions, particularly changes in the federal funds rate target or announcements regarding QE/QT, directly influence bond yields across the maturity spectrum. Simultaneously, the bond market provides crucial signals that inform the Fed’s policy decisions. Market-based measures of inflation expectations (derived from comparing yields on nominal Treasuries and TIPS), the overall level of interest rates, the shape of the yield curve, and credit spreads all provide insights into economic conditions and market sentiment that the Fed closely monitors. Furthermore, market expectations of future Fed actions are a powerful driver of current bond yields, as investors constantly try to anticipate the future path of monetary policy.

C. The Bond Market as an Economic Barometer

Beyond its roles in funding and policy transmission, the bond market serves as a vital real-time indicator of economic health and investor expectations. Movements in bond yields, especially Treasury yields, encapsulate the collective wisdom (or sentiment) of market participants regarding future economic prospects.

- Gauging Growth and Inflation Expectations: A pattern of rising bond yields often suggests that investors anticipate stronger economic growth and potentially higher inflation in the future, leading them to demand greater compensation for lending money. Conversely, falling yields frequently signal investor caution, perhaps reflecting expectations of an economic slowdown, lower inflation, or a “flight to safety” during times of uncertainty.

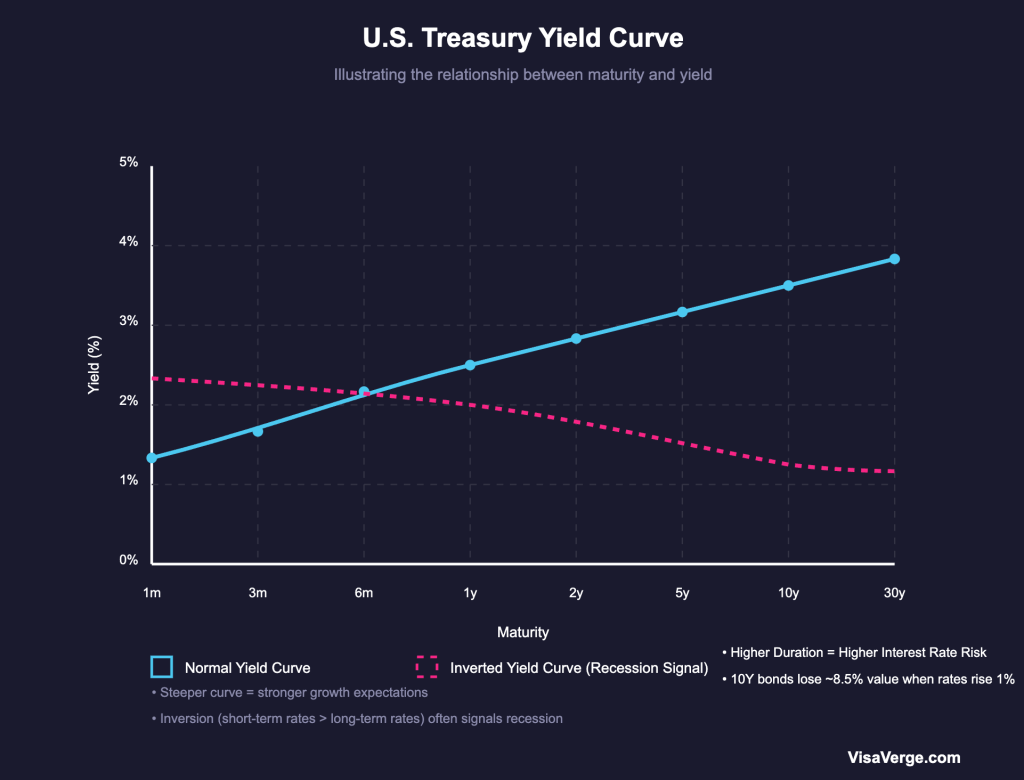

- The Yield Curve: The yield curve, which plots the yields of bonds with identical credit quality but different maturity dates (typically U.S. Treasuries), is a particularly powerful indicator. Normally, the yield curve slopes upward, meaning longer-term bonds offer higher yields than shorter-term bonds. This positive slope reflects a “term premium”—extra compensation investors demand for the added risks (like inflation uncertainty and interest rate volatility) associated with tying up money for longer periods.

- Yield Curve Inversion: An “inverted” yield curve occurs when short-term Treasury yields rise above long-term Treasury yields. Historically, this phenomenon has been one of the most reliable predictors of subsequent economic recessions in the U.S.. The logic behind this predictive power is often tied to expectations about monetary policy and the economy. An inversion might signal that investors expect the Fed to cut short-term interest rates significantly in the future to combat an anticipated economic downturn, pulling down current long-term yields. Alternatively, it could reflect market expectations of very low future inflation or even deflation. Common measures monitored for inversion include the spread between the 10-year Treasury yield and the 3-month Treasury bill yield, or the spread between the 10-year and 2-year Treasury yields. While a powerful signal, analysts caution that correlation is not causation, and the relationship might evolve, especially given unconventional monetary policies.

- Credit Spreads: The difference in yield between corporate bonds and Treasury bonds of similar maturity is known as the credit spread. This spread reflects the additional compensation investors demand for taking on the credit risk of the corporate issuer. Widening credit spreads generally indicate increasing investor concerns about corporate financial health or rising risk aversion, often observed during periods of economic stress or slowdown.

The bond market acts as a crucial intersection point for U.S. fiscal policy (driven by government spending and borrowing needs ) and monetary policy (managed by the Federal Reserve to influence interest rates and liquidity ). These two powerful forces meet and interact within the Treasury market. For instance, large-scale government borrowing (a fiscal action) can put upward pressure on interest rates, potentially conflicting with the Fed’s objectives if it aims to keep rates low (a monetary goal). This might necessitate Fed intervention, such as increased bond purchases (QE), to absorb the excess supply and manage yields, highlighting the intricate feedback loop between fiscal decisions and monetary operations.

The evolution of the Federal Reserve’s policy toolkit further complicates this dynamic. Beyond traditional tools, the Fed now employs administered rates like IORB and ON RRP, large-scale asset purchases (QE) and sales (QT), and forward guidance (communicating future policy intentions). The implementation and subsequent unwinding of these unconventional measures, such as managing the size of the Fed’s balance sheet or the level of funds in the ON RRP facility , can have significant and sometimes unpredictable effects on bond market liquidity, term premiums, and overall yield levels. This adds new layers of complexity and potential volatility for market participants to navigate.

The yield curve stands out not just as a snapshot of current rates but as a powerful gauge of collective market expectations about the future. Its shape reflects consensus views on future economic growth, inflation trends, and, critically, the anticipated path of Federal Reserve policy. The curve’s historical ability to predict recessions stems largely from this forward-looking nature—an inversion often signals that the market anticipates future economic weakness necessitating Fed rate cuts. However, because it is driven by expectations, the yield curve can also be influenced by shifts in sentiment that may not ultimately prove correct, or by technical factors such as large-scale asset purchases by the central bank, which can distort traditional relationships like the term premium. Therefore, while an invaluable indicator, the yield curve requires careful interpretation in conjunction with other economic data.

Municipal Bond Types Comparison

| Characteristic | General Obligation (GO) Bonds | Revenue Bonds |

|---|---|---|

| Security/Backing | Full faith, credit, and taxing power of the issuing government entity | Revenue generated from the specific project or source that the bonds financed |

| Repayment Source | General funds or dedicated property taxes | Project-specific revenues (e.g., tolls, fees, utility payments) |

| Typical Projects | Schools, roads, public buildings, general infrastructure | Toll bridges, water/sewer systems, airports, hospitals, housing projects |

| Relative Credit Risk | Generally lower | Generally higher (depends on project success) |

| Voter Approval | Often required | Typically not required |

| Special Categories | Limited-tax GO, Unlimited-tax GO | Private Activity Bonds, Conduit Bonds |

VI. Impact on American Individuals and Households

The operations and fluctuations within the U.S. bond market have direct and significant consequences for the financial lives of American individuals and households, affecting both their savings and investments, and the cost of borrowing money.

A. Bonds as Investment Vehicles: Savings, Retirement, and Income Generation

Bonds represent a fundamental asset class for individual investors, offering avenues for pursuing various financial goals such as saving for retirement, generating a steady stream of income, or preserving capital.

- Direct Investment: Individuals can purchase bonds directly. This includes buying U.S. Treasury securities through the government’s TreasuryDirect platform or purchasing municipal and corporate bonds via brokerage accounts. Holding individual bonds provides the owner with predictable income through regular coupon payments and the return of the principal amount when the bond matures, assuming the issuer does not default. U.S. Savings Bonds (Series EE and I) are another form of direct investment specifically tailored for individuals, offering safety and certain tax advantages.

- Indirect Investment: For most individuals, exposure to the bond market comes indirectly through investments in bond mutual funds or bond exchange-traded funds (ETFs). These funds pool money from many investors to purchase a diversified portfolio of bonds, managed by professional investment managers. This approach offers immediate diversification, reducing the risk associated with any single bond defaulting, and provides access to a wider range of bond types (e.g., Treasury funds, municipal bond funds, corporate bond funds, international bond funds, or broad-market funds like those tracking the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, often called the “Agg” ). However, these funds charge management fees and other expenses.

- Role in Diversification: A key reason individuals include bonds in their investment portfolios is for diversification. Historically, bond returns have often exhibited low or even negative correlation with stock market returns. This means that when stock prices fall, bond prices may rise or fall less significantly, helping to cushion the overall portfolio’s value during market downturns. As investors approach retirement or other financial goals where capital preservation becomes more important, they often increase the allocation to bonds and decrease the allocation to stocks in their portfolios. However, it’s worth noting that the correlation between stocks and bonds is not always negative and can turn positive, particularly in environments of rising inflation and interest rates, potentially reducing the diversification benefit.

- Household Assets: Bonds, held both directly and indirectly through funds, constitute a meaningful portion of the financial assets owned by U.S. households. Data from 2023 suggested bonds directly held accounted for about 8.6% of liquid financial assets, with mutual funds (holding both stocks and bonds) representing another 16.5%. Retirement savings accounts, such as Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs), 401(k) plans, and pensions (both private and government), are major holders of bonds and bond funds, making bond market performance critical to the retirement security of millions of Americans.

B. Influence on Consumer Borrowing Costs: Mortgages, Auto Loans, Credit Cards

The conditions in the bond market, particularly the level of yields on U.S. Treasury securities, have a direct and significant impact on the interest rates that consumers pay when borrowing money for major purchases.

- Mortgage Rates: The link is particularly strong between yields on longer-term Treasury securities (especially the 10-year Treasury Note) and interest rates on fixed-rate home mortgages. Lenders often use the 10-year Treasury yield as a benchmark when setting rates for 30-year fixed mortgages. When Treasury yields rise, fixed mortgage rates generally follow suit, increasing the cost of buying a home and reducing affordability. Conversely, when Treasury yields fall, fixed mortgage rates tend to decline, making homeownership potentially more accessible. The actual mortgage rate offered to a borrower is typically the benchmark Treasury yield plus a “spread”. This spread accounts for various factors, including the lender’s operating costs and profit margin, fees (like servicing and guarantee fees), and compensation for the additional risks associated with mortgages compared to Treasuries (like credit risk and prepayment risk). Dynamics in the market for Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS), including buying activity by the Federal Reserve (QE or QT), also significantly influence this spread and thus the final mortgage rate paid by consumers. It’s important to note that adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs) are typically tied more closely to short-term interest rates, which are more directly influenced by the Federal Reserve’s federal funds rate target.

- Other Consumer Loans: The influence extends beyond mortgages. Yields on Treasury securities across different maturities serve as benchmarks that affect the interest rates charged on other forms of consumer debt, including auto loans, student loans, and personal loans. Generally, a higher interest rate environment in the bond market translates into higher borrowing costs for consumers for these types of loans as well.

- Credit Card Rates: While credit card interest rates (APRs) are often variable and directly linked to benchmark rates like the Prime Rate (which moves in lockstep with the Fed funds rate), the overall level of interest rates shaped by the bond market can indirectly influence the baseline from which these rates are set.

- Economic Ripple Effect: The impact on borrowing costs has broader economic consequences. When rising bond yields lead to higher interest rates for consumers, it can discourage spending, particularly on interest-sensitive big-ticket items like homes and cars. It also increases the cost for businesses to borrow for investment. This dampening effect on consumption and investment can slow overall economic growth. Conversely, lower interest rates resulting from falling bond yields can make borrowing cheaper, potentially stimulating consumer spending and business investment, thereby boosting economic activity.

The state of the bond market, therefore, is far from an abstract concern for financial professionals alone. It directly touches the financial lives of ordinary Americans through multiple channels. Changes in bond yields affect the value of retirement savings held in 401(k)s, IRAs, and pension funds. Simultaneously, these same yield movements determine the interest rates paid on mortgages, car loans, and other forms of debt, significantly impacting household budgets and purchasing power. Fluctuations in the bond market translate into tangible financial gains or losses and influence major life decisions for millions of households across the country.

The connection between the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield and fixed-rate mortgages serves as a primary and highly visible transmission mechanism. This linkage directly connects sentiment and pricing in the global bond market to the affordability of housing, a critical sector of the U.S. economy and the largest asset for many American families. Understanding the factors that drive not only the base Treasury yield but also the spread between Treasuries and mortgage rates—including MBS market dynamics and Federal Reserve interventions —is essential for assessing the outlook for the housing market and its broader economic impact.

Furthermore, while bonds have traditionally served as a valuable diversification tool against stock market volatility , this relationship is not immutable. Recent periods have witnessed a rise in the correlation between stock and bond returns, particularly when yields are rising amid inflation concerns. When both asset classes move in the same direction, the diversification benefit is diminished. This forces investors and financial advisors to re-evaluate traditional portfolio construction strategies and potentially seek alternative assets or approaches to manage risk, especially in macroeconomic environments characterized by high inflation or coordinated monetary policy tightening across asset classes. The assumption that bonds will always act as a “safe haven” during equity downturns requires careful scrutiny based on prevailing market conditions.

Bond Investment Risk Types

| Risk Type | Description | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Interest Rate Risk | Risk that rising interest rates will cause bond prices to fall. Longer-maturity bonds have higher interest rate risk. | Ladder maturities, focus on shorter-duration bonds, hold until maturity, consider floating-rate bonds |

| Inflation Risk | Risk that inflation will erode the purchasing power of fixed bond payments and principal. | Consider TIPS, floating-rate bonds, shorter maturities, higher coupon bonds |

| Credit/Default Risk | Risk that the issuer will fail to make interest payments or repay principal when due. | Diversify across issuers, focus on higher-rated bonds, monitor issuer creditworthiness, consider government bonds |

| Liquidity Risk | Risk that a bond cannot be sold quickly at or near its fair market value. | Focus on larger issues, more actively traded bonds, or Treasury securities; plan holding periods |

| Call Risk | Risk that the issuer will redeem the bond before its scheduled maturity when interest rates fall. | Consider non-callable bonds, analyze call protection periods, demand higher yields for callable bonds |

| Reinvestment Risk | Risk that coupon payments or returned principal must be reinvested at lower prevailing rates. | Consider zero-coupon bonds, ladder maturities, match bond maturities with investment time horizon |

U.S. Bond Market Size and Composition (2025)

| Market Segment | Outstanding Value (Trillion USD) | Percentage of Total |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. Treasury Securities | $28.3 | 60.3% |

| Corporate Bonds | $11.2 | 23.9% |

| Municipal Bonds | $4.2 | 9.0% |

| Federal Agency Securities | $2.0 | 4.3% |

| Other | $1.2 | 2.5% |

| Total U.S. Fixed Income | $46.9 | 100% |

VII. U.S. Treasury Yields: The Benchmark Rate

U.S. Treasury yields, representing the interest rates paid on debt issued by the U.S. government, hold a unique and central position in the financial world. They serve as critical benchmarks influencing other interest rates, financial market valuations, and economic activity both domestically and globally.

A. Relationship with Other Financial Markets (Equities, etc.)

Treasury yields, particularly the yield on the 10-year Treasury Note, function as a fundamental reference point for pricing a vast array of other financial assets.

- Equity Markets: Treasury yields are a key input in many equity valuation models, often used as the base “risk-free” rate in discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis to determine the present value of a company’s expected future earnings. All else being equal, lower Treasury yields reduce the discount rate applied to future earnings, making those future earnings more valuable today and potentially boosting stock prices. Conversely, higher Treasury yields increase the discount rate, which can put downward pressure on stock valuations as the required rate of return for holding risky assets increases.

- Dynamic Correlation: The relationship between Treasury yields and stock market performance is complex and not always inverse. Sometimes, rising yields coincide with falling stock prices, possibly because higher yields signal tighter monetary policy, increased borrowing costs for companies, or a “risk-off” shift where investors sell stocks to buy safer Treasuries. At other times, however, yields and stocks can move in the same direction. For example, if yields are rising because of strong economic growth expectations, this optimism can also boost corporate earnings forecasts and drive stock prices higher. Recent history has shown periods of positive correlation between stocks and bonds, particularly when inflation concerns drive yields higher. Understanding the underlying reason for the yield movement—whether it’s driven by growth expectations, inflation fears, or policy changes—is crucial for interpreting its likely impact on equities.

- Corporate Bonds: Yields on corporate bonds are directly linked to Treasury yields. They are typically quoted and analyzed as a “spread” over the yield of a Treasury security with a comparable maturity. This spread represents the additional yield investors demand to compensate for the credit risk of the corporate issuer compared to the risk-free Treasury. Therefore, changes in Treasury yields form the base upon which corporate borrowing costs are determined; a rise in Treasury yields generally leads to a rise in corporate bond yields, increasing funding costs for businesses.